Where do poinsettias come from? How the plant became so closely connected to Christmas

The history of poinsettias

How did the poinsettia get so closely connected with Christmas? LiveNow from FOX talked to Julie Weisenhorn, an extension horticulture educator at the University of Minnesota, to learn more.

Poinsettias have become as much of a holiday tradition as Christmas trees, but how did the vibrant plant get so closely connected to Christmas?

Julie Weisenhorn, an extension horticulture educator at the University of Minnesota, sat down with LiveNow from FOX’s Stephanie Coueignoux for a lesson on the popularity of poinsettias.

Before Weisenhorn shared the poinsettia’s holiday history, she settled the debate on how to pronounce it: you can say poinsett-uh or poinsett-iuh.

Poinsettias, a Christmas tradition (Photo by Marcus Brandt/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Origins of the poinsettia

The cultivation of the plant dates back to the Aztec empire in Mexico 500 years ago.

MORE: A day in the life of Santa Claus’ reindeer

Among Nahuatl-speaking communities of Mexico, the plant, in the Eurphorbia family, is known as the cuetlaxochitl (kwet-la-SHO-sheet), meaning "flower that withers." It’s an apt description of the thin red leaves on wild varieties of the plant that grow to heights above 10 feet (3 meters).

"It used to be actually sold as cuttings and cut flowers," Weisenhorn explained.

Poinsettia plants (Euphorbia pulcherrima) are being displayed ahead of the Christmas season in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, on December 9, 2023. (Photo by Creative Touch Imaging Ltd./NurPhoto via Getty Images)

In 1909, Paul Ecke Sr. got the idea to grow them as seasonal plants at his ranch in southern California.

"And it’s been a three-generation business, and he really, really kind of made this plant be part of our Christmas season," Weisenhorn said. "Part of it is the color red. But also we see poinsettias in cream and pink, and even some of the spray-painted blue and green and other purple colors and kind of weird stuff."

What else to know about poinsettias

Weisenhorn said despite popular belief, poinsettias are safe to have in the home.

MORE: Elf on the Shelf creator got ‘permission’ from Santa Claus to start iconic holiday tradition

"A lot of people think that they're poisonous, and so they refrain from having them in their house, but they're actually not," she said. "They're very little bit mildly toxic. So if your dog bit off the leaf, it might get a little bit of an upset stomach."

Customers shop for poinsettias plants at La Nochebuenas De Mexico nursery in Tlajomulco De Zuniga, Mexico, on Friday, Dec. 9, 2016. Photographer: Cesar Rodriguez/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Weisenhorn cautioned, however, about poinsettias’ sticky, milky sap, which can harm your furniture and can also cause mild dermatitis if it gets on your skin.

Why the poinsettia’s name is controversial

Nearly 200 years after the plant was introduced in the U.S., attention is once again turning to the poinsettia’s origins and the checkered history of its namesake, a slaveowner and lawmaker who played a part in the forced removal of Native Americans from their land. Some people would now rather call the plant by the name of its Indigenous origin in southern Mexico.

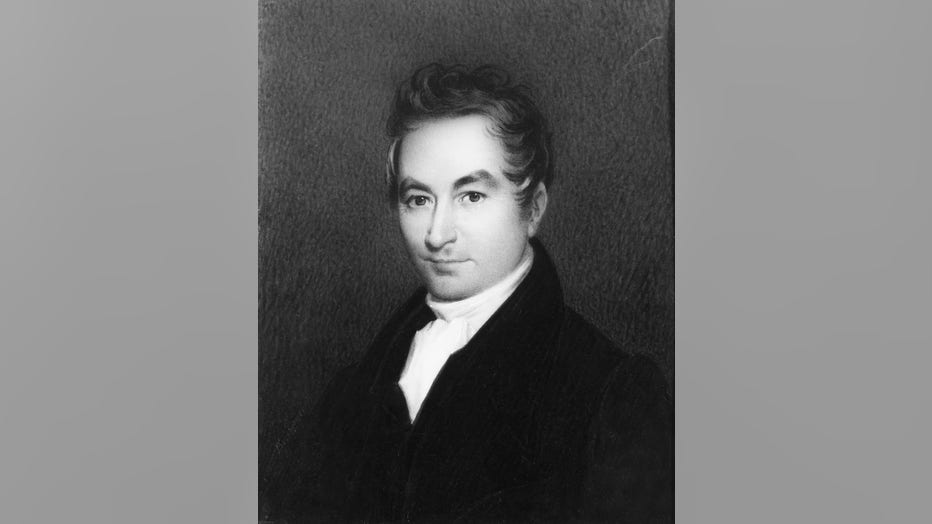

The name comes from the amateur botanist and statesman Joel Roberts Poinsett, who happened upon the plant in 1828 during his tenure as the first U.S. minister to the newly independent Mexico.

Joel Roberts Poinsett, 1843. Artist Hugh Bridport. (Photo by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images)

Poinsett, who was interested in science as well as potential cash crops, sent clippings of the plant to his home in South Carolina and to a botanist in Philadelphia, who affixed the eponymous name to the plant in gratitude.

A life-size bronze statue of Poinsett still stands in his honor in downtown Greenville, South Carolina.

As more people learn of its namesake’s complicated history, the name "poinsettia" has become less attractive in the United States.

Unvarnished published accounts reveal Poinsett as a disruptive advocate for business interests abroad, a slaveholder on a rice plantation in the U.S., and a secretary of war who helped oversee the forced removal of Native Americans, including the westward relocation of Cherokee populations to Oklahoma known as the "Trail of Tears."

(Photo by Mario Villafuerte/Getty Images)

"Because Poinsett belonged to learned societies, contributed to botanists’ collections, and purchased art from Europe, he could more readily justify the expulsion of Natives from their homes," historian Lindsay Schakenbach Regele wrote in a new biography titled "Flowers, Guns and Money."

Though he was a slaveowner, he opposed secession, and he didn’t live to see the Civil War.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.